It is the light falling continually from heaven which alone gives a tree the energy to send powerful roots deep into the earth. The tree is really rooted in the sky.

—Simone Weil, ‘Human Personality’

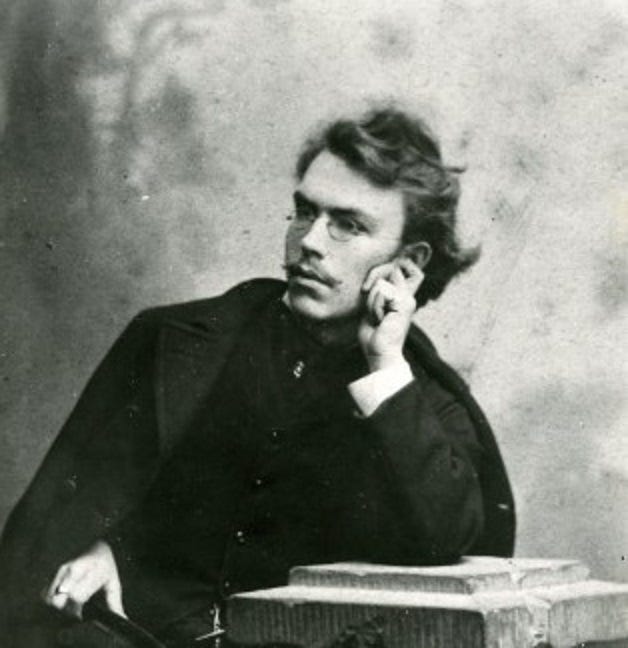

In the autumn of 1870 Philipp Mainländer completed the second and final volume of his magnum opus, The Philosophy of Redemption. It was an oddly optimistic title for an astonishingly pessimistic work, effectively cobbled together from darker elements of Christian cosmology, gnosticism, Kant, Neitszche and Schopenhauer. Mainländer’s thesis, however, belongs to a unique species of capital-P Pessimism that makes Schopenhauer seem positively merry.

God, according to Mainländer, fundamentally abhors being. In His perfection, He is disgusted by the fundamental imperfection of being, so much so that He embodied himself into a universe—this universe, the one that I share with you—that tends toward chaos, decay and death. As creation decays and dies, so does God. We are all inexorably entwined and spiralling into oblivion together with His abominable creation, from the murky imperfection of being into the perfection of unbeing.

Our role, our obligation, is thus to aid in the decay of the universe; rage against the foetid chaos of life and hasten the onset of cosmic decay and death. Death is Mainländer’s titular “redemption”.

But at the bottom, the immanent philosopher sees in the entire universe only the deepest longing for absolute annihilation, and it is as if he clearly hears the call that permeates all spheres of heaven: Redemption! Redemption! Death to our life! and the comforting answer: you will all find annihilation and be redeemed!

We are all but the suffering viscera of a suicidal God who longs only for annihilation. Among other things, Procreation becomes a mortal sin. Mainländer’s antinatalism is so much more militant than Malthouse, or his environmentalist inheritors; darker, even, than the rationalist nihilism of a Rust Kohl doom-sayer. To be alive, let alone to create life, is fundamentally bad; an insult the very essence of God.

Were he better known, Mainländer would be the posterboy of the school shooter. Trenchcoats in summer. Nine Inch Nails on repeat, precociously depressed, world-weary, alone in a crowd. At the nineteenth century German Pessimist dinner party that we must assume is happening in Purgatory, Mainländer, were he to be invited at all, stays not for schnapps and strudel.

When the first edition of The Philosophy of Redemption arrived from the printer, Mainländer arranged the copies into a neat stack on the floor of his modest home in Offenbach am Main. He then climbed atop the stack and hanged himself until he was dead. He was thirty seven years old.

The idea at the bottom of The Philosophy of Redemption is clearly abhorrent, which is likely a large part of the reason why there exists no definitive english translation, and why Mainländer himself is confined to purgatorial corners of Nihilist reddit. But this very abhorrence invites the question of why we find it so abhorrent. Mainländer, deeply troubled though he might have been, was simply attempting to decipher that which is most fundamental: that which it is to be. After all, if one is to ask any question, surely the biggest and best and most German question is the one that we all have in common. Much can be held against Mainländer, but in the end the poor bastard was simply cutting to the chase. What is it to be? To my mind, his solution is more elegant than most: being tends toward death, and death is Good.

There have been, of course, manifold attempts before and since Mainländer resigned himself to his own solution. Let’s invite a selection to that German Pessimist dinner—call it a Symposium—and tell them each to bring a plate.

The Liberal shows up late. They suggest that to be is to be steeped in various woolly-headed ideals—franterity, liberty, family, duty, “rights” and such. All of them hopelessly entangled, all of them clumsy and unsatisfying stand-ins for old time religion. They bring a rotisserie chicken that they’re pretending to have roasted themselves.

The Conservative is right on time. They insist that heritage is the only thing we have in common. The precise nature of that heritage varies according to each individual conservative’s proximity to the means of production, and invariably spirals into ideals at least as woolly-headed as those trotted out by the Liberal. They nevertheless thought it only polite to bring a nice casserole (they pronounce it cassoulet) and a well-matched bottle of red.

The Hegelian will proffer some baffling jargon and conclude with an unsatisfying and overly complicated dialectic that terminates with Napoleon strutting through Vienna on horseback. They bring a failed soufflé that tastes better than it looks.

The Darwinist is slightly late, but apologetic. They declare that we all share a drive to propagate genetic information, that the main character is the code in our cells, blindly piloting the flesh. Compelling, airtight, empty. They bring a protein shake.

Somehow, the Buddhist shows up more or less on time, despite not quite knowing what the time is. They gently report that to be is to suffer. We are possessed of will and desire, the frustration of which is universal. The Liberal loudly and performatively eats it all up with a spoon. (The sole Schopenhauer fancier also runs with it. He wasn’t invited, but he came anyway to roll his eyes at the Hegelian and secretly leer at the women). The Buddhist brings boiled, unseasoned potatoes, devoured ravenously, if last.

The Postmodernist shows up halfway through dinner. They take everybody aside separately, each time and in a different way insisting that confusion is all we have in common. A coherent common ground doesn’t exist—in its place is a morass of entangled perspectives. I’m not exactly a card-carrying Postmodernist, but I do have a lot of fun at their parties. They bring store-bought caramel popcorn.

The Marxist is late. They blame the Liberal. They suggest that the labour theory of value is all we have in common, and to leave it at that. They’re right, but everyone is low key annoyed they had to point it out. They brought just as much as the Conservative, but they ate half of it on the bus.

We all know what the Freudian brought. They think it’s hidden, but we can all tell it’s right there under the dinner table. They showed up weirdly early.

The aesthete is fashionably late, cheerful, if a bit tubercular. They insist that beauty is all there is, or all that’s worthy at least. The pursuit of beauty feels like a moral imperative because it is a moral imperative. We strive onward, towards the infinite, towards the transcendent (the Hegelian looks up from his failed soufflé), imagining and re-imagining ourselves; a cosmos of humanity observing and taking pleasure in its own manifold splendour. A compelling stance, but it feels awfully fattening. They bring, I don’t know, let’s say, a croquembouche.

One must imagine the Existentialist happy just to be there. To be is to be, and that’s that. They only bring cigarettes, which everybody agrees is fine, actually.

All of these solutions are, of course, less horrifying than that of Mainländer. But are any of them as elegant? The Existentialist answers the Dane’s question in the affirmative, while Mainländer is firmly in the ‘not to be’ camp. Framing the question as such introduces an ethics—is it right and good to be, or shall we endeavour not to be?—which is arguably the reason we find Mainländer’s nihilism so abhorrent, yet so hard to refute. The assertion is not only the existence of a universal Wille zum Tode, but that such a death drive is also good.

* * *

In the winter of 2016 Katie Barber and I opened a group exhibition at what was then the Australian Experimental Art Foundation. What the exhibition was about—because it was, as is anything embarked upon by young curators, steeped in a shameless kind of aboutness—was elusive, some might say hopelessly ineffable. Some—including, at the time, Barber and I—would say the show was about ineffability itself. Most—my current self included—would call the rationale for the show hopelessly pretentious. The title, Dug and Digging With, gave little away. An early, shortlisted title was slightly more helpful: Being Itself.

What we wanted was a white cube gallery full of original pieces that, while not exactly exemplifying that ineffable quality of being, could conceivably—if they were to be somehow superimposed upon each other, or arranged into a certain gestalt—reveal at least the shape of something universal. One artist, Julia McInerney, had a pair of reading glasses ground down into a fine powder, then deposited onto the gallery wall such that they were effectively invisible. It was in the same vein as an older work of hers, which consisted of a small gallery flooded with water, upon the surface of which floated an aluminium anchor that had been similarly ground to a fine powder. She called that one The Meadow (Virginia Woolf Piece), after the author’s suicide by wading into a river with coat pockets laden with stones.

Another artist, Matt Huppatz, fabricated two large cubes from transparent, slightly iridescent perspex, filled one of them with glycerin vapour, then connected the two via a hollow tube, such that the vapour would slowly diffuse from one cube to the other.

Another artist found a hollow brass pipe, about the size of a large cigar, among some bins in an industrial part of town. He then crammed cheap, store-bought caramels into both ends and hung it from the gallery ceiling by a single strand of fine sterling silver string. Over the course of the exhibition, the wadded caramel dripped out of each end of the pipe in the manner of slow pitch, at a rate of one imperceptibly slow drop every few days. He titled the piece ‘Hail Mary’. He also produced a site-specific piece called ‘Blended Rubber Trumpets Under a Car Seat’, which consisted of the words blended rubber trumpets under a car seat, clearly, but discreetly written backwards on the gallery ceiling.

Some five years earlier, the same artist—Tom Squires—submitted for his graduate show a monolithic stack of 108 canvases stretching precisely to the ceiling of the gallery, all of them blank, all of them stacked face to face, such that the surface of each canvas was in the purest darkness. Squires called the piece ‘Model for Philipp Mainländer’.

* * *

I have no formal religious faith, but I am wont to concede that there is something spooky going on with respect to what can only be described as the sensation of being; that which metaphysicians and cognitive scientists call the “Hard Problem”, and psychologists reduce to “theory of mind”, or otherwise pathologize as “solipsism”—a conviction that one’s own perspective is all there is. As a child, I had no name for the phenomenon—if you could call it a phenomenon—but I knew it was real and I knew it was perfectly and ineffably strange.

I am trapped within my own perspective, so thoroughly and so inexorably that I am convinced that this perspective—that of the first person—is the only perspective. How, after all, can there be more than one first person? We, each of us, experience the world this way, as if through the eyes of the sole protagonist holding the sole camera, knowing yet somehow incapable of fully comprehending that every other being is the centre of their solipsistic universe, trapped behind their camera.

My earliest memory of this contradiction came around the age of five, watching the parallax of the moon as I walked, knowing that the way it moved relative to the landscape was mine and mine alone, even though the people around me were equally convinced that this travelling moon was theirs and theirs alone. It was a lonely feeling, itchy and peculiar, and it has never fully left me.

It was this feeling that I wanted those nine artists to get to the bottom of in Dug and Digging With. They wrestled bravely, but they ultimately failed. This, I suppose, is the story of secular culture after the enlightenment; myriad individuals grappling in the dark. We all know what we’re looking for, but the only way to describe it is by the shape of our various failures to find it.

* * *

Besides the lunar parallax, for some time, and for all its abhorrence, I found in Mainländer the most elegant synthesis of the first person conundrum. I didn’t agree with it, but for certain periods in one’s early twenties, at certain dark hours of the night, one’s predicament tracks disturbingly well with the idea that we, all of us, are the decaying and tortured viscera of a dying god.

For years, I only periodically suffered the impasse, occasionally glimpsing a way forward, but for the most part—Dug And Digging With aside—brushing off the whole conundrum as a kind of stoner naivete. There comes an age when mysteries feel less urgent—leave noumena to the noumenal, clean your room, learn a trade, get on with the film.

It was essayist and mystic Simone Weil who made the first person problem alive again. A French Jew at the height of her powers during the Second World War, Weil is every bit as earnest and compelling as Mainländer—possessed of a deeply masculine obsession with Platonic truth, cursed with an excruciating ability to identify and empathise with the suffering of others, Weil embodies a strange, uniquely twentieth century synthesis of mysticism and hard-nosed Pessimism. Most of her intellectual life was occupied by an almost myopic pursuit of the meaning and purpose of that which it is to be. The question consumed her like no other, and what made it all the more compelling was the fact that Weil, like Mainländer, would finally succumb to it.

Summarising Weil’s short life forces one to take her as seriously as any of her intellectual contemporaries. Camus described her as “the only great spirit of our time”. De Beauvoir, despite being so at odds with Weil’s pious mysticism, admired her extraordinary sense of empathy—hers was “a heart that could beat across the world”. Weil was an ardent socialist who had no truck with Stalinism, a devout Catholic who refused to be baptised into the Church—doggedly convinced that there could be no capital-T truth in the collective; nothing truly fundamental in any earthly or institutional consensus. Democracy, human rights, the scientific method—all the trappings of liberalism—as noble as their intent might be, could only ever be secondary to that which was fundamental. It was the pursuit of this fundament that possessed her so utterly, reaching a powerful and uncompromising apotheosis in her final essay, ‘Human Personality’.

You can read the rest of this essay in Volume III of Agony. Purchase your copy at agonymagazine.com