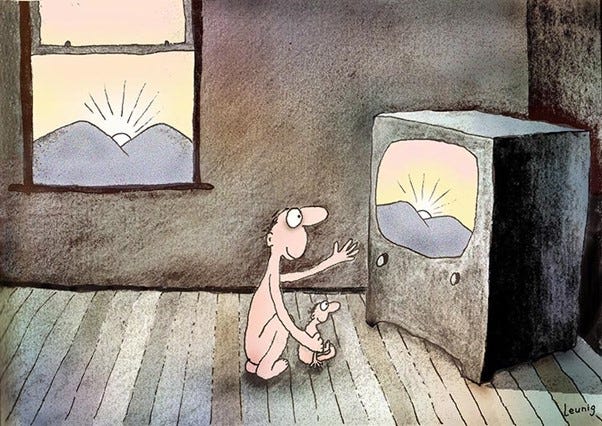

Philosophers have spent centuries debating what they call “the mind-body problem”, but are yet to capture its gist as acutely as this drawing:

The works of Descartes and the many who have followed him groan under the weight of their laboured arguments and clumsy prose. But here, a simple image – giving every impression of something thrown off in an idle moment – expresses what the more cerebral, scientific philosophers do not imagine. Not just the mechanics of how stuff – matter and soul, brain and mind – interact, but the human predicament that gives rise to the ‘problem’ in the first place. That problem is less an intellectual conundrum than a personal experience that partly defines human life. On the one hand we are animals, both enabled and burdened by our bodies and ruled by their immediate urges. But on the other hand, as human beings, we are capable of postponing gratification, of reflecting on our passions, and of mental travel that take us to distant and even merely imagined places and times, unfettered by our gross flesh.

The image is the work of the Australian cartoonist Michael Leunig who died in Melbourne just before Christmas, aged 79. The Butterfly Catcher – its richness deserves a name (all the names I shall use for his cartoons are mine) – is representative of a vast body of work he produced, mainly for daily and weekly newspapers and magazines, over sixty years. But then it is true to say that most of his individual works are representative of that body, not because they are tediously sameish or repetitive, trundling off a production line, but because they employ an instantly recognizable, idiosyncratic style, and because – while covering a huge range of topics, many of which, like his biting political commentary, I shall ignore – he returns again and again to the profoundest elements of the human condition. Alienation, for example:

This is more than a comment on urban anomie, electronic distraction, and so on. At one level it resembles the allegory of the cave from Book VII of Plato’s Republic. Man is not just an alienated creature, but a blinded and enslaved one, captive to the titillating play of images which are shadows of a puppet show but which he mistakes for reality. Plato anticipates the Christian view that our alienation is not just a product of industrial technology or of large-scale human social life – important as these are – but is a deep-seated estrangement endogenous to our humanity, and not treatable by social engineering, re-immersion in nature, or by the new enthusiasm for flight to other planets. We live in a confection of reassuring illusion and a life seriously led is one struggling to free itself from its tendrils and escape from the cave to the sunlight of reality.

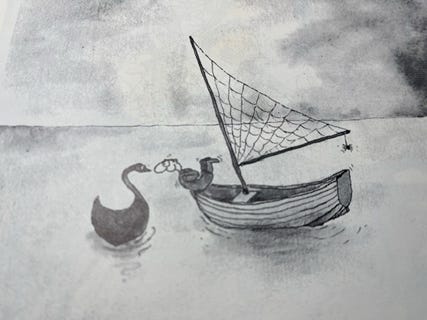

This might seem pessimistic, but it is only one side of Leunig’s work. The typical Leunig character – when not purely a villain or a victim – is unashamedly naked, a puny figure against the vastness of nature (or sometimes an industrial or urban landscape) imposing either in its beauty or its menace. He is typically solitary, and sometimes lonely. He can be frightened and he can also be cruel. But very often he is a being at peace with the world, by which he is perpetually astonished. He looks at the world, as G.K. Chesterton would put it, with all the wide-eyed fascination of a baby. He is a survival from Eden, an innocent abroad in a fallen world he cannot comprehend but always delights in. He is more than eccentric; he is from another universe – and yet he is us. Animals abound in the cartoons as witnesses to our folly or partners in our joy – or victims of our cruelty – serving as echoes of the prelapsarian condition. This man talks to them – and they talk back, or at least commune with us:

There is something of this man in each of us, which perhaps is why he is drawn anonymously, without distinguishing individual features. He and the other characters show that we are animal yet human. That we are innocent and yet we are guilty. That we inhabit a world that is not our home. That our lives juxtapose joy and sorrow, as does one Leunig cartoon to the next.

It has been said that his work is theological. Sometimes it was overtly so. But it is worth studying all his work, because the defining elements of human life they identify are the basic ingredients of a religious picture of the world, prior to any system of metaphysics. Returning to The Sunset, to speak meaningfully of being estranged from God, we must be able to speak generally of estrangement from nature, from one another, and, as in The Butterfly Catcher, from ourselves.

Here are more such ‘ingredients’. There is longing and disappointment in The Peacock, where a man and woman wait patiently for a peacock to spread its feathers, but it does so only after they walk away. There is the loneliness of the crowd in Ship Ahoy where two men in small boats cry out to one another from a distance as they sail on a sea of humanity. There is resentment in At the Dance where people trapped in cages of their own rancour gaze enviously at a pair who have thrown off their cages to dance happily together. And here is a telling image of our lostness in materialistic fantasy:

In his introduction to The Penguin Leunig (1974) comedian and savant Barry Humphries wrote of Leunig that “his jokes are all poetically conceived and that is why they touch the heart as surely as they make us laugh”. There is something Chaplinesque about Leunig’s humble little men and women. Chaplin was the master of the comedy of pathos. His reputation has endured because ‘the little tramp’ moved us to laughter and tears simultaneously. Likewise in Leunig comedy joins with tragedy in the capacity to show the human condition in the light of a compassion that mixed grief and delight.

In the 1990s Leunig’s work turned explicitly to religion and indeed to poetry in the genre of prayer. He also produced paintings and wrote newspaper articles. But cartoons remained his most effective medium. This is one of the profoundest I know:

Nietzsche was out of date. Man had already killed God long before the philosopher announced the deity’s passing. And not only in Palestine 2000 years ago. Leunig realized that each of us recapitulates that murder in our own heart. The question is whether the sequel– resurrection, rebirth – will also follow in our hearts.

The statement announcing Leunig’s death said movingly: “the pen has run dry, its ink no longer flowing”. That pen and ink blended joy and sorrow in a body of work that was popular without being ephemeral, in touch with the abiding human concerns that the specialist so often loses touch with. He created a world where each of us is chasing that butterfly – a symbol of the Peaceable Kingdom – with part of us nervously wondering if it is just the invention of our own heads. He was always realistic about that ambivalence of lives lived under the shadow of mortality. His men are never supermen. He never forgot for whom the bell tolls:

Andrew Gleeson is an Australian writer and erstwhile philosopher.