The desire for objective truth found in the work of great Greek philosophers can be seen also in the work of the Greek builders of the ancient world. The Doric, Ionic and Corinthian orders each originated in various tribes of ancient Greece, although they were subsequently used around the Greek world in the Classical and Hellenistic periods for their stylistic associations rather than tribal affiliations. The orders demonstrate the ancient Greek instinct to see the world as a relationship of proportioned and harmonious parts. A simple post and beam construction heightened to the level of the sublime – Greek temple architecture was so successful at speaking truth to human aesthetic sensibilities that it spread through the Mediterranean world, was adopted by the Romans and later the Europeans, until eventually we see it every day on the streets of Adelaide, Australia.

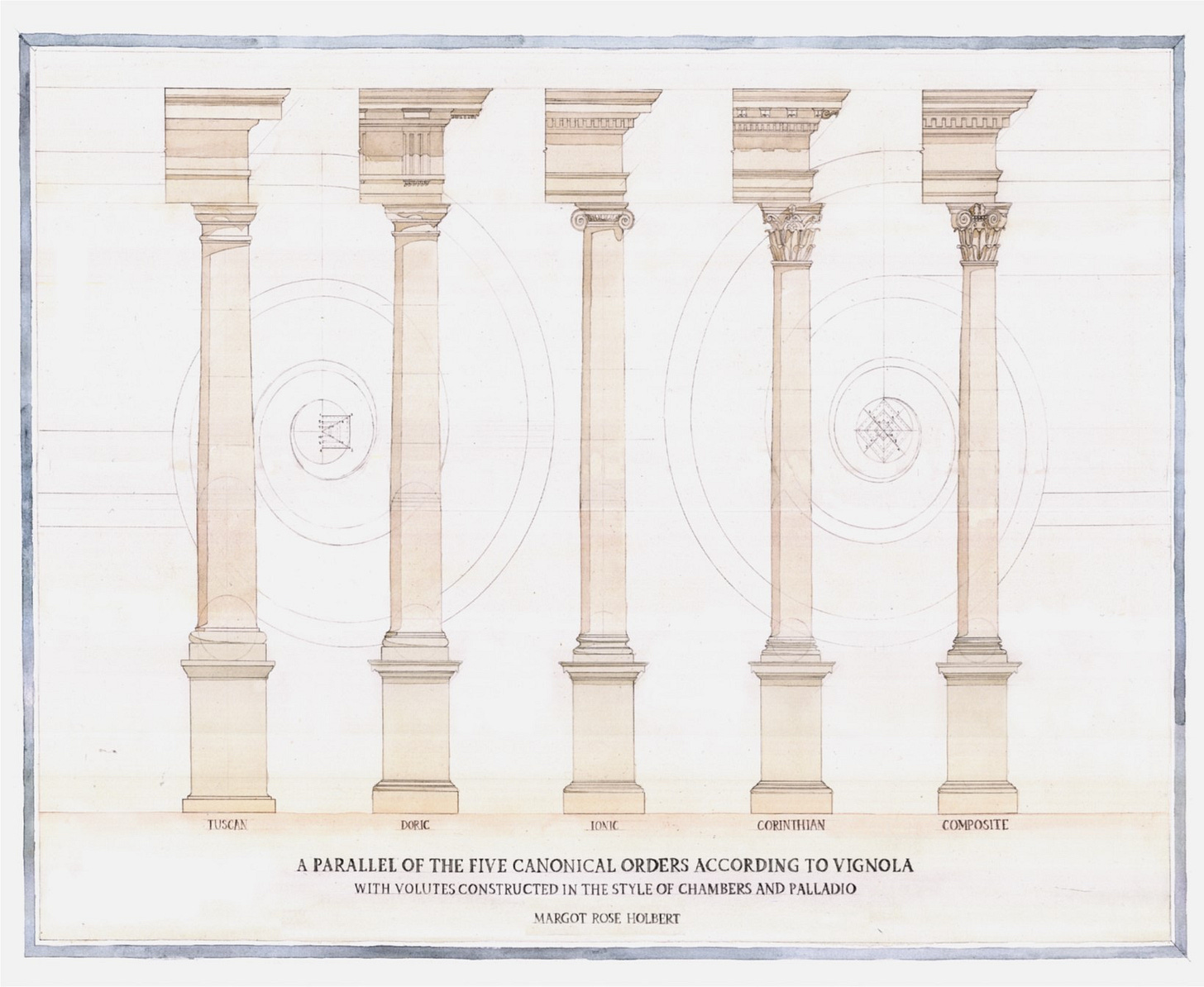

Above is an illustration of the classical orders in parallel; Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian and Composite, drawn in the style of the Renaissance architectural theorist, Vignola. It is important to understand that the orders are not simply some popular classical column capitals. The capital is the distinctive marker of an order, however, it is only one part of what makes an order unique. In the Renaissance you might have easily come across a building with no columns at all and known that it was designed in the Ionic order, and in ancient Greece you might have stumbled upon some ruins in the wilderness and known from a piece of crumbling cornice that this was once an immense Corinthian temple. This is because each order is primarily a proportioning system- with every element of a building corresponding to each other element. Each detail, from the height of the column shaft, to the size of the frieze or the curve of the cornice is proportioned with respect to the diameter measurement of the column (whether the column is applied or not), and the capitals therefore represent the proper kind of decorative treatment for each kind of proportion.

No one definitive code determined the proportioning of those ancient Greek temples, and yet certain rules of thumb were always followed by ancient builders to strive for a harmonious, and objectively beautiful, architecture. The right proportions were arrived upon intuitively. For example, Doric decorations were best suited to a slightly thicker column shaft and heavier looking proportions than the Ionic or the even more attenuated Corinthian. The Doric order is said to hint at more primitive timber methods of post and beam construction, with its simple and dignified decorative elements each representing in stone what would have been in timber. For example, the triglyph – the vertical bars that decorate the Doric frieze – is said to represent the end of a transverse secondary beam, with the guttae beneath representing the little nails securing the beam to the architrave, or primary beam, below. The visual demonstration of structural soundness is given symbolically in the case of the triglyph, but is also shown more essentially in the very form of all classical architecture; the way the shape of each capital graciously accepts the load of the beam above, the neck of the column like a collar, containing the force and directing it down the shaft, which swells like a muscle (known as entasis) before discharging through the wide base firmly into the ground. This visual expression of structural translation is known as tectonics, from the Greek tekton meaning carpenter, with the architect being the arkhi-tekton, or chief carpenter.

The Romans, familiar with the Greek style of temple building seen across the Mediterranean, chose to adopt this Greek style of building to represent their empire, using the orders in civic buildings, bath houses, palaces, and of course their own temples. The Romans expanded upon the three Greek orders, adding the modest and rustic Tuscan (a simplification of the Doric) and the slender and decorated Composite (a combination of the Corinthian and Ionic orders). The Romans favoured the Corinthian order for its festive nature, and it became a symbol of the victories across their empire. Vitruvius, the Roman architectural theorist, in his treatise on architecture tells a fanciful story about how the Corinthian order came about, which I think is quite charming:

A young Corinthian girl of citizen rank, already of marriageable age, was struck down by a disease and passed away. After her burial, her nurse collected the few little things in which the girl had delighted during her life, and gathering them all in a basket, placed this basket on top of the grave. So that the offering might last there a little longer, she covered the basket with a roof tile.

This basket, supposedly, having to have been put down on top of an acanthus root. By springtime, therefore, the acanthus root, which had been pressed down in the middle all the while by the weight of the basket, began to send out leaves and tendrils, and its tendrils, as they grew up along the sides of the basket, turned outward; when they met the obstacle of the corners of the roof tile, first they began to curl over at the ends, and finally they were induced to create coils at the edges.

Calimachus who was called Katatexitechnos by the Athenians for the elegance and refinement of his work in marble, passed by this monument and noticed the basket and the fresh delicacy of the leaves enveloping it. Delighted by the nature and form of this novelty, he began to fashion columns for the Corinthians on this model, and he set up symmetries, and thus he drew up the principles for completing works of the Corinthian type.

A copy of Vitruvius’ De Architectura was discovered in 1414 in the library of the Abbey of St Gall and Renaissance architects in Italy were fascinated by the codification of the classical orders provided by this Roman author. Though he provided no illustrations, Vitruvius’ descriptions of the proportioning systems used by the Romans were comprehensive. Leon Battista Alberti published Vitruvius’ treatise as a part of his own De re aedificatoria in 1450, in which he clarified some of Vitrivius’ work with his own codification of the orders. This encouraged other architects and architectural theorists to write their own treatises on the most correct way to construct the classical orders. Sebastiano Serlio published his own heavily illustrated treatise in 1537, Vignola published his in 1562, and Palladio his in 1570.

The image above shows the orders drawn in accordance with the proportioning system provided by Vignola and clarified by William Ware in his publication The American Vignola (1903). Each order is depicted with a pedestal supporting a column with entablature above. Each column has a base and a capital, and each entablature is made up of an architrave, frieze and cornice.

To give a brief description of the construction process – I have divided the space between the ground line and the top of the entablature into 19 parts. The pedestal is made of four of these parts, the column twelve, and the entablature three. In the space designated for the column I can now work out my column width for each order. For the Tuscan order, the base diameter is 1/7 the height of the column, for the Doric the diameter is 1/8 the height, for the Ionic the diameter is 1/9 and for the Corinthian and Composite the diameter is 1/10 the height. After establishing the column base diameter measurement for an order, every other element of the order can be determined, for example according to Vignola, the height of the Doric capital is half the column base diameter, and the Ionic cornice is 7/8 as high as the Ionic base diameter.

The five orders as codified by the Renaissance architects are useful tools in designing and proportioning Classical architecture. You don’t really want to go making your building proportions any stockier than the Tuscan, and you also don’t want to make your proportions much more slender than the Corinthian or Composite. The five orders can provide you with a calculable window of ideal proportions for achieving both structural soundness and aesthetic beauty.

But I still hope for a day when we can train our eyes to that ancient Greek intuitive sensibility.

This essay appeared in Volume II of Agony.